4 Ways to Prevent Harm from Surgical Staplers

If you’ve been following medical device safety issues this year, there’s a good chance you’ve seen the headlines about patient injuries and deaths related to internal surgical staplers. The devices are commonly used in many high-risk surgical procedures. Misuse and malfunction of surgical staplers can lead to serious complications—as we’ve seen during our own research and accident investigations.

The stapler cases we investigate tend to be associated with serious injuries or fatalities, some of which could have been prevented. The overall adverse event rate is low relative to the number of times staplers are used; however, cases of preventable death are chilling. This has led ECRI Institute to thoroughly research and evaluate staplers and to publish safety hazards to our members. In fact, surgical staplers have appeared twice on our annual list of Top 10 Health Technology Hazards— first in 2010 and again in 2017.

So, why is this decades-old technology in the news now? And, more importantly, what can you do to keep patients safe?

A recent report by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) summarized 109,997 problem reports submitted for surgical staplers and staples since 2011. This figure includes reports submitted to FDA's publicly accessible Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database, as well as those submitted to its "hidden" Alternative Summary Reports (ASR) database.

Of these, there were 412 deaths, 11,181 serious injuries, and 98,404 malfunctions. Also in this report were results from a systematic literature review including 207 surgical stapler studies on malfunctions during use—some of which resulted in hemorrhage and/or conversion to an open procedure.

The considerable evolution of surgical staplers over recent years and the uncovering of these reports prompted the FDA to consider reclassifying the devices. FDA convened a Medical Devices Advisory Committee meeting in late May, and invited me to present ECRI Institute’s surgical stapler surveillance data to a panel of independent experts.

The outcome was agreement that internal surgical staplers should be reclassified as Class II devices, instead of the more lightly regulated Class I. Accordingly, FDA has begun identifying "special controls" that can be shown to reduce risks with the use of surgical staplers—a necessary step for a device to be upclassified from Class I to Class II.

While this reclassification—and, more importantly, the implementation of effective special controls—should be a step forward to improve patient safety, this process will take time. Fortunately, hospitals and providers don't need to wait.

By understanding how staplers work, recognizing how complications occur, and involving various stakeholders in patient safety efforts, hospitals and providers can make a difference.

Staple and cut mechanism

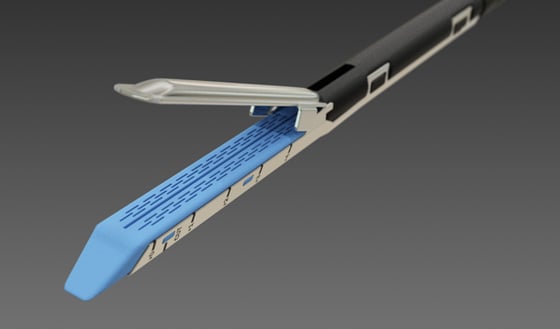

Internal surgical staplers are available in different designs for different applications. Linear staplers, for example, are used to seal and transect (staple and cut) internal tissue during endoscopic surgical procedures, such as organ removals, as well as for bariatric and other gastric surgeries. Circular models are most commonly used for GI anastomoses.

Linear designs consist of a handle and shaft with jaws at the end that can be closed on the tissue of interest (picture the jaws of an alligator). The surgeon clamps onto the tissue and then fires the stapler. This action deploys rows of staples into the clamped tissue on either side of the intended cut line, followed immediately by a knife that transects the tissue in between those staple lines. In this way, the stapler seals the tissue on either side of the cut to prevent hemorrhage. Circular models, by comparison, include a circular anvil that is compressed against the end of a cartridge to seal and cut the tissue of interest.

Complications

Bleeding or GI leaks can occur if a staple line is incomplete or does not hold. Such problems may be immediately apparent, or they may not appear until sometime later, leading to severe symptoms long after the patient has been closed up and sent for recovery. Patient harm in these events can range from no injury to fatality. We've found that, in most cases, the stapler actually functions as intended. The adverse consequences instead result from clamping on another instrument or clip, clamping on tissue that is too thick or too thin, or some other form of misuse. Poor staple line integrity can also occur with diseased, necrotic, or ischemic tissue.

Four steps to reduce harm

Here are key recommendations that we advise hospitals and providers to take now.

- Improve event reporting. A common complaint about FDA’s MAUDE and ASR databases is that the information they provide is incomplete or inaccurate. There are two main things that risk managers and patient safety professionals can do to improve the quality of event reports. First, do more than just follow the minimum reporting requirements—update reports as new information is obtained. For example, an event that is initially classified as a stapler “malfunction” (without injury) should be updated if an associated injury manifests days later. Second, establish an investigation plan. Risk management and frontline clinicians should know what to sequester, and should implement measures such as labeling disposables according to the chronology of their use and saving loose staples.

- Consider the user when making purchasing decisions. Supply chain and purchasing departments should consider user familiarity when making a large purchasing decision, such as switching an entire fleet of staplers from one manufacturer to another. Lack of user familiarity continues to be a contributing factor in investigations and problem reports. Involve the user in purchasing decisions to bring potential use issues to light before devices are placed into service.

- Recognize risks and plan ahead. Users of these surgical staplers should appreciate the risk of immediate and serious hemorrhage in vascular applications. We encourage users to have a back-up intervention planned in case of hemorrhage. Such resilience can dramatically reduce patient harm.

- Improve user training. Ensure that surgeons are knowledgeable and experienced with the device. Usability among staplers can vary from one model to the next. Unexpected outcomes are less likely if the surgeon is knowledgeable about and experienced with the device before use. Develop appropriate training criteria for staplers with the manufacturer and ensure these are met prior to use of the stapler.

Reclassification by FDA and the identification of special controls is a step in the right direction. But it is just a step; and FDA is just one of the stakeholders with a role to play. Manufacturers can continue to improve device designs, building in more "forcing functions" that reduce the risks of use. And healthcare facilities can implement measures like those outlined above to prevent patient harm.

We just wrapped up a podcast that answers many more questions about surgical staplers and how they work, so please take a listen. Then, tell us what you think. What are your concerns with surgical staplers? What would you like to see improved? You can reach me at accidents@ecri.org.